Archive

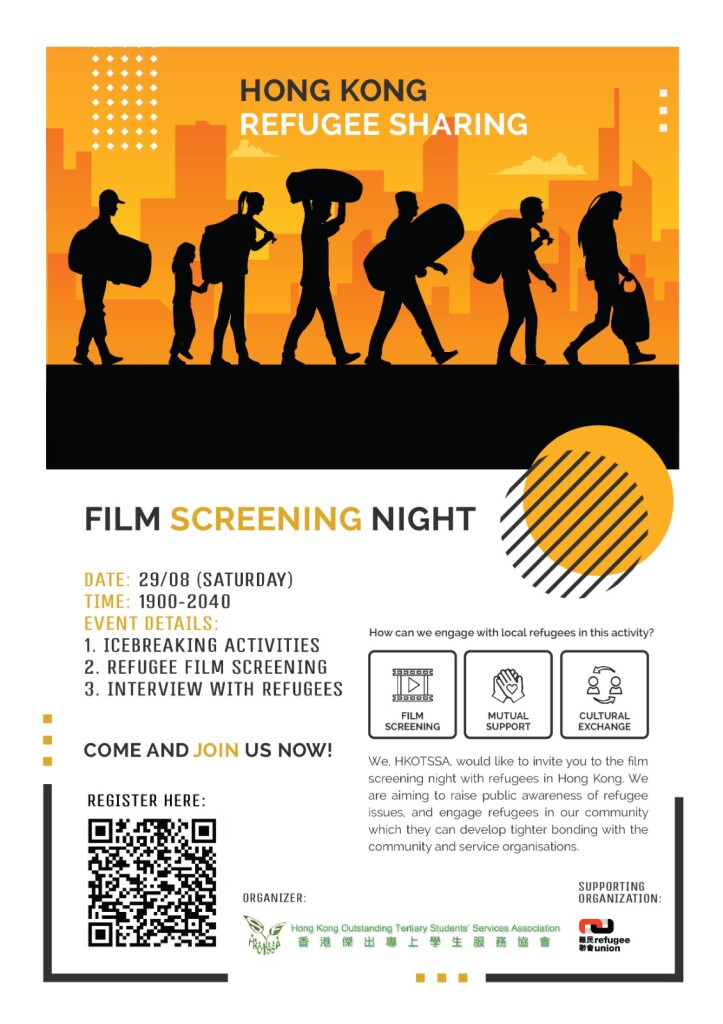

Hong Kong Refugee Sharing

Aug 25th, 2020 | Personal Experiences, Refugee Community, RU updates, programs, events | Comment

Profiles of asylum: From the ancient city of Mosul to Hong Kong

Aug 6th, 2020 | Detention, Immigration, Personal Experiences, Refugee Community, Rejection | Comment

“Mosul is an ancient city. It was actually called Nineveh before. Have you heard of it?” Alex told me. Most people heard of Nineveh, a Biblical city with a name that echoes across millennia, bubbling with history and myth and revelation and, most recently, a cycle of occupation and violence to match its historic stature. Alex continued, “Before the American occupation in 2003, we could go out with our friends and have picnics outside. It was safe. Some people used to go camping. It was totally safe. It was a good place.”

During 254 days of detention in 2014, Hong Kong Immigration officers at Castle Peak Bay Immigration Centre asked Alex repeatedly why he had left his country. “They suspected that I was a terrorist when they found out I came from Iraq. Then I told them about my past incidents, one with Islamic State, another with the US Army and then another with the Iraqi Forces. I told them life was worse than hell. I think they got scared. Imagine, they don’t know who you are and you have no documents and you’re telling them about life in a war-torn country full of massacres that I witnessed with my own eyes …”

After fleeing from violent conflict in Iraq in April 2010, Alex traveled from Turkey to Cyprus to Malaysia to Indonesia to Singapore to South Korea and finally, in 2014, he reached Hong Kong. Along the way he experienced a series of detainment, interrogations, beatings and the occasional act of kindness. As he described his experiences, he was describing the life of someone outside of the law, someone whose attempts at finding hope and peace are impeded by the structures set up to determine the validity of his claims, structures which deal with him and other refugees primarily as criminals. “What I have faced, what I have suffered, what I have seen … the pain that I’ve felt, it’s really hard to express.”

When a person applies for asylum in Hong Kong, they are administered by the Unified Screening Mechanism (USM), a process designed to determine the validity of their claims. Alex had no passport to prove he was an Iraqi citizen, nor help from an embassy. He explained, “Immigration killed my case. They totally rejected my identity. They said my Iraqi identity is not accepted. They said we can only accept you as an ‘Arabic speaker.’ I mean, does that make sense? I asked them, where am I from?”

So there was Alex, a young man from an ancient city, who had once worked alongside his father installing windowpanes in Mosul’s quiet suburbs, now an undocumented “Arabic speaker” with no recognized history of citizenship or travel due to his decision to leave the very country which makes him a suspect. The choice to flee from violence and to put himself through hardship and uncertainty becomes not admirable and courageous, but suspicious. During his 9-month detention, Alex was humiliated, beaten, and kept in solitary confinement over ten times. He was losing his mind, losing his sense of self and purpose. Alex experienced his lowest points in Hong Kong’s detention system.

“The hardest times I faced were when they kicked me into the solitary confinement cell. That killed me from inside. It made me want to commit suicide. If you look at that cell there’s no window, there’s no one to talk to. It is full of mosquitoes and cockroaches walking on the wall and ceilings everywhere. The lamp in the ceiling was always on hurting my eyes when I tried to sleep. I used to ask the officers to switch it off and they refused. I felt lower than an animal. It felt like they were taking revenge against me for some reason.”

Why is a safe city like Hong Kong so undesirable for those seeking asylum? “In this city I cannot go here and there as I have no money. I mean if I have nothing to do where can I go, what can I do? In Hong Kong refuges are not allowed to work. We are not allowed to have income. We are not allowed to get a bank account, to do any basic things in life.” Then there is the question of hope. More than a decade into exile, Alex is no closer to what he set out to achieve. “I believe anything is possible in this world, but it is hard for me to expect any positive things in Hong Kong. There are a lot of refugees with good skills but there is no encouragement. It seems the government does everything to discourage us and crush our hopes. Basically, they don’t want us to be well.”

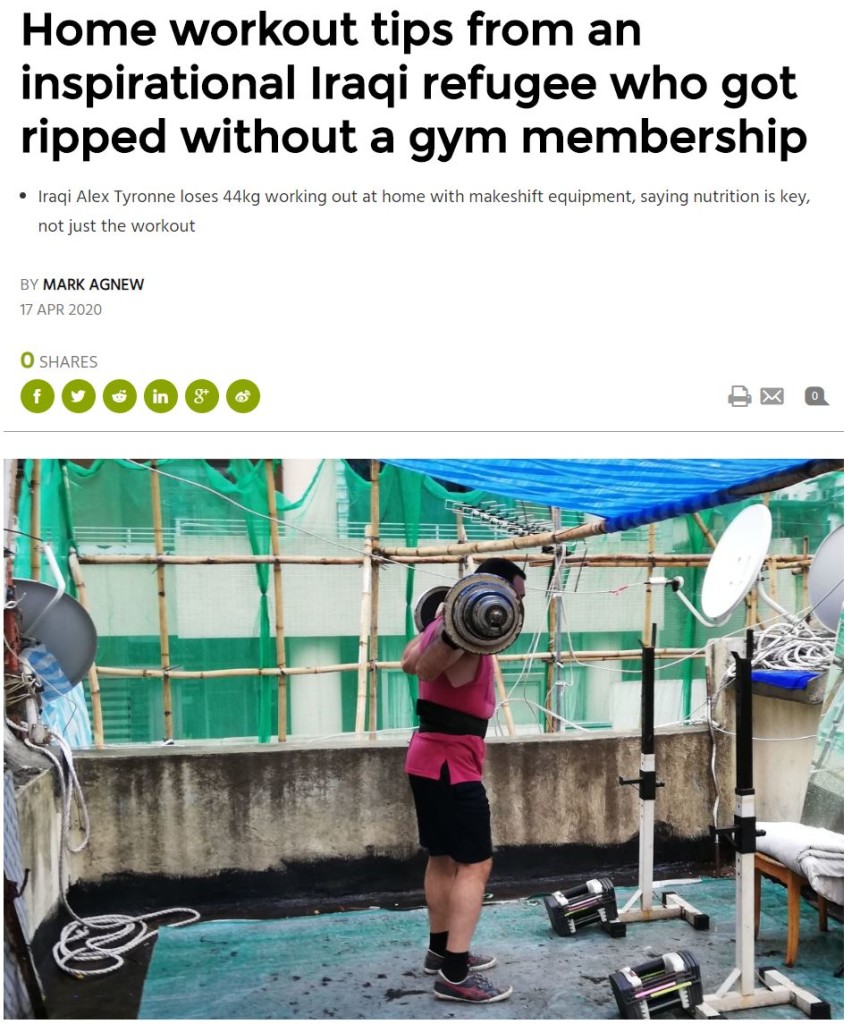

Despite this, Alex balances despair with optimism by choosing to face the reality of his situation and his role in managing his physical and mental health. After his release from detention, Alex chose to do for himself what no one could do for him staying positive, keeping healthy and helping those around him. He found a supportive community amongst Hong Kong’s asylum seekers and activists. Through the Refugee Union Alex has met “good people that give me real respect and make me feel like I’m human. There’s no discrimination. There’s no racism. There’s no animosity. There’s no hatred. That’s perhaps what makes me feel that life is still beautiful. Refugee Union has helped me a lot. It’s about how to relieve your stress, how they make sure to create fresh hope in life, not to increase tension, not to make you more depressed, not to make you want to give up. Forget about all your troubles, we’re going to try to help you or at least keep you busy and make you feel that life is still good.”

Even with a community of friends, however, there are limits to how much Alex can allow himself to feel free and at peace. “I really don’t want to focus on my case in Hong Kong any more. I will start to overthink. I will start to worry and get anxious. I mean there are a lot of negative things. It is really better for me just to leave this case aside. Six years in Hong Kong and nothing has moved forward. I lost hope in Hong Kong Government. I really don’t have any hope for another opportunity.”

(written by Pedro Cortes)

Meeting refugees at the union

Jul 15th, 2020 | Personal Experiences, Refugee Community | Comment

Tom* sought asylum in Hong Kong twenty years ago. He is from Pakistan and met his wife here during this time. They now have four children (16, 10, 8, 5 years old) – all asylum-seekers. While Tom used to work in construction back home, he has not been able to work at all in Hong Kong. Under the city’s law, refugees are banned from working, though many choose to pursue illegal jobs to make ends meet. However, in response to this, Tom said: “I cannot pursue illegal work, I do not dare – what will happen to my wife and children if I go to jail?” But without employment, living in limbo has taken a toll on him: “My life is empty,” he tells me, “Twenty years. I’m wasting my time. I only bring my children to school and back, nothing else to do.” There are tears in his eyes as he speaks and I have to look away.

When asked what the most difficult aspect of refugee life is, Tom sighs: “Life is hard here because everything is so expensive.” Just recently, his youngest daughter’s school decided to change the uniforms. However, he could not afford the new uniform and had to ask the school if they could delay the payment for a month. Luckily, the school was able to let Tom’s daughter stay in school, but Tom frets over where to find the money for the fees. Refugees live on a scant $3200 monthly from the government, often finding themselves lacking sufficient income. Parents, like Tom, are under enormous pressure to provide for their children in the notoriously expensive city of Hong Kong.

Yet many have also found solace in this city. Hannah* is a Ugandan refugee: “I came to Hong Kong hurt and broken,” she says. Hannah has since converted from Islam to Christianity, which played a pivotal role in her life: “I would have been dead, but God heard my prayers.” Though initially her life in Hong Kong was difficult, Hannah has now found a community at her church, friends who supported her when she was admitted to hospital and money for treatment was scarce. “If you believe in God, anything is possible,” she beams, “I’ve let go of my troubles. I appreciate what I can achieve. I know God has a plan.” Hannah now volunteers at the Refugee Union, a place she describes as a safe haven that listens to the voices of the marginalized. “How can I not help when they’ve helped me?” she asks. “Everyone should put their feet in another person’s shoes and feel their life.”

Anne* is also an Ugandan refugee, once a teacher back home. She came to Hong Kong a decade ago in search of safety away from the authoritarian regime under Yoweri Museveni. “The big difference between Uganda and Hong Kong is that here there is security and the rule of law. In Uganda, people go out one day and don’t come back. People die silently. I had to leave. If you have any power, you must. If you don’t find a way out, you will be dead.” Anne herself had her land and property taken away forcefully by the government. She cannot return to Uganda as she fears she will be labelled a terrorist and thrown in jail and possibly tortured. “We are trying to tell the truth, but now we are the government’s enemies,” she shakes her head.

Under the iron fist of the dictator, corruption, censorship and violence plague Uganda. “Uganda shouldn’t be a poor country. It is only because of poor leadership and management. The President doesn’t develop the country at all. He came to steal, kill, destroy and spoil our future. He treats human lives as a business.” As a mother back home, Anne finds it painful to watch the news, because it reminds her of her family and her people. “We’ve lost our futures, we’ve lost everything. In our heads, we are still connected to Uganda. Sometimes we become insane thinking about this. I cry in my sleep, because all I want is for my people to be safe and to be free. Is that too much to ask?”

* names were changed for privacy reasons

Written by Sophia Zhang (16) – Shatin College

Workout tips from our hardest training member

Apr 17th, 2020 | Health, Media, Personal Experiences, Refugee Community | Comment

How a Hong Kong refugee is empowering women with art collective

Aug 21st, 2019 | Media, Personal Experiences, Refugee Community | Comment

Mini Acts for the Greater Good is bringing paintings by refugees from all over the world to Hong Kong

Sep 4th, 2018 | Personal Experiences, RU updates, programs, events | Comment

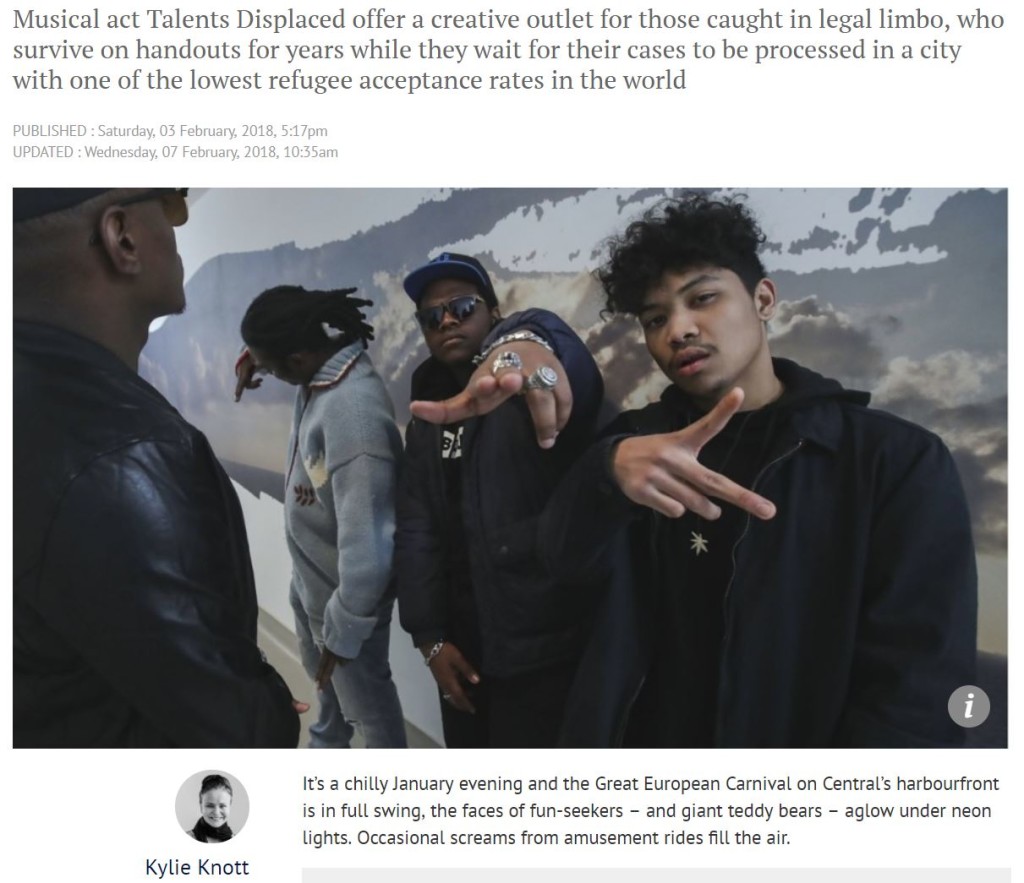

Hong Kong refugee musicians put on hip-hop shows – a form of release while they’re stuck in bureaucratic limbo

Feb 8th, 2018 | Personal Experiences, RU updates, programs, events | Comment

The ‘Heartbreaking’ Plight of Undocumented Children in Hong Kong

Apr 19th, 2017 | Advocacy, Government, Immigration, Legal, Personal Experiences, Refugee Community, Welfare | Comment

Denying Refugees Right to Work is Catastrophic

Apr 12th, 2017 | Advocacy, Crime, Detention, Government, Personal Experiences, Racism, Refugee Community, Rejection, Welfare | Comment