Archive

Profiles of asylum: When she’s older I can’t always be around for her

Oct 4th, 2020 | Crime, Personal Experiences, Refugee Community | Comment

Dara slammed the home door shut and pressed her back against it as her daughter’s hand clenched with fear around her wrist. Yells and screams resounded from the men in the street below, so furious they seemed to make the walls shake. Dara knew that she and her daughter were powerless if these men wanted to enter her home yet a part of her still clung to the belief that by leaning against the door, her daughter would be better protected.

As the sound of hurried footsteps drew nearer, her daughter’s fingers cinched tighter. Although Dara could feel her hand slowly weakening, she was thankful to feel her daughter’s grasp. The words yelled in the corridor were unrecognizable. Perhaps because muffling by the door, perhaps because they were foreign, for these men were also asylum seekers; or perhaps because they were so drunk they had little self-control in their speech.

Dara looked at her daughter who had now thrown herself onto her, wrapping her arms around her waist, thrusting her head into her stomach, as if trying to block out the noise. “Go.” Dara whispered, “Stay on the bed and do your homework.” Arms slowly loosening from Dara, the girl lugged a laden school bag from under the table, and pulled out her homework. This was the usual drill for the two when fights broke out: listening together at the door until it dragged on for so long that it was better for her shaken daughter to be distracted by something else. Then, Dara would have to listen, anticipate, guess at the men’s every move. It was something she had grown to be accustomed to.

Hong Kong is often referred to as one of the safest cities in the world. With security cameras covering almost every street, this image of chaos is not the one that comes to mind for most people. Indeed, the area where Dara and her daughter live is most definitely not representative of the city as a whole, but moving here was a difficult decision that the mother had to make in the search for a better living. Their last home was a dingy room in the center Kowloon, right in the hustle and bustle. There were positives and negatives of living there: the good being that everything they ever needed -school, grocery stores, transport links- were accessible, but the bad being that rents were incredibly high. They shared a bathroom with the twenty who lived on their floor, some elderly living alone and other asylum-seekers. That room was acceptable when Dara’s daughter was smaller, but as she grew older, now eight years old, the space was insufficient and a poor environment to study. Thus, they decided to move away.

The footsteps grew louder. Dara could feel the floorboards of her apartment vibrate with the men’s footsteps. A burley man, perhaps in his late twenties, passed Dara’s door. Behind his back, he held a package wrapped in a piece of dirtied black cloth. The package had the length and width of a long ruler. A feeling of dread swept over Dara as she already knew what the package was even half hidden from sight. Thankfully the man did not stop at Dara’s door, instead continued upwards, shifting his grip on the package so that he now clenched one end of it in his fist. Dara stopped looking. There was no point anymore. She already foresaw the ending of that frightening incident.

As Dara returned to join her daughter who was now engrossed in her schoolwork, a dreadful scream rose from above then something metallic clattered onto the floor. The cold sound, like that of an out of tune cymbal, of dropping metal rang through the whole building and momentarily captivated attention. After that, there was nothing: no yells, no commotion. It was as if everything had once again returned to how it usually was.

The next day, as Dara went up to the garbage room, she found the man’s hidden package lying on the floor. Cautiously, she kicked aside the cloth that shielded it. Underneath it, lay a blade: long, sharp, and blood stained. There were splatters of blood, but no body. Where was the victim? Who was he? What fury had come between him and the assailant? Dara had no answers.

During our interview, Dara frequently circled back to this incident, clearly an issue that troubled her. She expressed that she was not overly worried about her own personal safety, for she “was already accustomed to dealing with people and seeing things like this” and that “a woman of her age would unlikely be of interest to those men”. Instead, she was more concerned for the safety of her daughter particular as she got closer to becoming a teenage. Dara said, “When she’s older I can’t always be around for her” and “as you know, girls of that age are more likely to attract trouble.” However, as her daughter is already well integrated in her school and doing very well, Dara is reluctant to relocate again. Thus, in the meantime, before there are any allowances for change, the two must remain vigilant all the time, especially at home.

Profiles of asylum: Frozen in place while time moves forward

Sep 27th, 2020 | Legal, Personal Experiences, Refugee Community, Rejection | Comment

In 2007 Arin was seven years old and his brother, Viraj, was five when they left their hometown to seek asylum in Hong Kong because their mother’s life was in danger. They were too young to know why they were leaving the Punjabi city of Amritsar or where they were going. “Maybe for a better future, but I didn’t know why my mother left home when I was little,” Arin says.

Viraj’s first impression of his new home was the lack of noise. “Hong Kong is quieter than Amritsar.” Also, India’s Punjab region is mostly flat, expansive farmland and Hong Kong’s steep hills proved a challenge for the two youngsters. The beginning of their story here sounds like the story of immigrants anywhere. Having no friends initially and struggling with the linguistic and cultural differences, they remember that teachers were nice to them at school and they felt welcome. As they became more fluent in Cantonese (and eventually mastered a total of six languages) they were able to make friends and associate with the local culture through music, television, and social media. “We had seven or eight good friends from Form 1 and we had Chinese friends and others from different cultures,” remembers Arin.

Growing up, Viraj played football with his school friends while, over the years, they became used to climbing the hills of the city together to get to school. They have come to see themselves as children of Hong Kong. Things seemed normal and school life was good, but “outside school we faced many difficulties,” says Arin. “We didn’t have enough money to eat. We usually asked other people for money. In the past, we received $2000 each month. It was not enough for three of us.”

“It was hard. Every month we had to report to Immigration and miss school. It’s good that [the government] gives us things, gives us money for rent and food. But it is not enough. We once lived in a ‘cube house.’ That was hard for us. It was a very small place.” The two siblings lived with their mother in a 100-square foot room in a subdivided flat, meaning that there was just enough space for a bed within the plywood walls. They shared a kitchen and bathroom with seven other tenants in their subdivided unit. They rented this “cube” for $4000 a month.

“We are glad that time is over. Now things are better.” The network of refugees and NGO’s in place to assist them has gone some way in meeting the needs of people whose are, as a matter of policy, neglected by the government. “In secondary school, we got some help from other people and had some pocket money to spend each week.” After thirteen years, these young adults in asylum must come to term with their harsh reality compared to the options enjoyed by their former resident classmates.

While the additional aid eases some of the stress of daily life, the legal restrictions of their refugee status define the limits of their aspirations and hopes for the future. Since graduating in January of 2020, they have been spending most of their time at home “because there’s nothing to do.” Today some of their friends are working, others went to university, but the brothers cannot think far ahead in the future. Even if they could afford it, they would not be allowed to work after furthering their studies. Since their mother requested asylum protection in 2007, the brothers are legally defined as illegal immigrants and, thirteen years later, their lives remain frozen in place while time moves forward.

“I want to teach young children someday, like in kindergarten,” Arin says. “Maybe in the future I will continue my studies. But not now. Now I just stay home because there is nothing to do.” Like many young Hong Kongers, he loves online gaming. He stays up until four in the morning on most nights playing Call of Duty or PUBG because he dreads waking up in the morning. Days are long when you have nothing to do, even longer when you cannot study or work like their resident friends. For Arin, Viraj, and other second-generation refugees, each day is a repetition of the one before and any attempt to change this is met with severe consequences. “We are not allowed, but if we tried, we could get a job,” one claims, acknowledging that if arrested it would mean 15 months in prison and a criminal record.

Despite the hardships, it’s remarkable to note that Arin and Viraj have nothing but positive things to say about Hong Kong. “Yes, I like the place. It’s good. The people here are nice and I am really glad that I learned Chinese and made some Chinese friends.” There is even the lingering sense of optimism and gratitude commonly felt by many immigrants: “My mother changed our lives. If we were in India, we would be nothing,” said Arin, affirming that his mother made the right decision for them. They ask only to be allowed the dignity to live and work and the recognition of their basic rights as human beings.

When asked if they want to return to India, Arin said, “of course, I want to go back to India someday to visit my grandparents and my family. But I cannot go until immigration lets us go. They should let us go to our home countries and come back but they only allow us to leave if we never come back.” Hong Kong is their home. If they cannot come back, they will not leave.

(written by Pedro Cortes)

Arin and Viraj are available for interviews and presentations at schools and universities.

For bookings please email info@refugeeunion.org

Profiles of asylum: Learning to let go

Sep 20th, 2020 | Personal Experiences, Refugee Community | Comment

Samuel held his breath as his phone squeaked monotonous beeps, each seeming lasting longer as he grew increasingly impatient. Finally, the beeps stopped and woman inquired, “Hello?” The slow drawl of the O and the silent H were unmistakable despite Samuel’s decreasing opportunities to hear them. Samuel did not answer, but merely pressed the receiver closer to his ear as if he did not want to miss the woman’s breath.

“Hello? Who is this?” she asked again. Samuel hesitantly replied, “It’s me, Mama. It’s Samuel in Hong Kong …” Then the line went dead. The woman had slammed the call shut before Samuel finished uttering the sentence. Samuel shook his head despondently and pocketed the phone with a sigh. This was not the first time his mother had shunned him. In fact, he had received this cruel treatment for twenty years, but nevertheless thought it was worth another try.

Samuel lay silently on the family bed shared with his wife and three children. He thought of his mother’s voice, the only person in the world who would not talk to him, yet the person he wanted to talk to the most. Religion had come between them: his mother had raised him a Muslim, but he had converted to Christianity. The reasons for completely cutting him out of her life were complex, but for his mother were serious enough to shun a son whom she presumably still loved.

His mother was not the only one to treat Samuel as an apostate. In fact where he grew up, violence was the reaction to Christian conversion. If Samuel and his family were to return to his hometown, it would cause a lot of pain for his extended family. Firstly, anyone who interacted with him would be punished, but, secondly, it would raise the threat of execution for his immediate family. It would be a public execution that would leave bloodstains on the street. The reality would be gruesome.

Samuel loves Hong Kong because the city accepted and protected his family. But, within this appreciation comes the frustration that persists for twenty years: he is not permitted to work. As a skilled construction worker who could maneuvering bulldozers and cranes back home, Samuel knows he is capable of earning money with his own two hands. He wishes he could support this wife and children through his own efforts, instead of relying on government welfare.

His inability to financially support himself vexed him terribly when he sat in the doctor’s examination room. “I’m sorry,” the doctor faltered, “We are unable to continue the treatment.” His eyes would not meet Samuel’s and instead fixated on the wall behind him. “Samuel, it’s your medical waver.” The doctor nodded slowly, “It only covers basic expenses. If you want to continue receiving treatment, you need to pay it yourself.” Samuel’s heart was hardened against the disappointment. He sat silently in the plastic chair, his fingers tightly clinched. He nodded, thanked the doctor then left without saying a word. No further explanation was required.

On the way home it wasn’t the first time Samuel was disappointed with his predicament. In essence, had his medical condition been life threatening, authorities had told him that they would rather watch him suffer. Luckily for Samuel, his medical conditions improved and life gradually returned to normal for the family. However, this normalcy did not persist for very long: Hong Kong’s street protests began again, hitting their lives especially hard as they resided near the urban area where many of the clashes occurred. Samuel’s sleep, already disturbed by sharing a bed with four people, continued to deteriorate. For many months, the blaring sound of sirens, shouting, and chants became bedtime songs for the family, teargas seeping through closed windows.

These events were regular turbulence in Samuel’s life: the shunning by his mother, the challenges of refugee life, the disappointment of his children, the limitation of medical services, the daily search for essential money, the endless waiting for a decision by Immigration were a rolling tide in his mind. Having survived in a merciless ocean for years, Samuel developed a coping skill that many don’t learn in a lifetime – he learned let go.

“I remind myself to let go,” Samuel explains. “I cry. I pray then let go of anything I cannot control. It is God’s plan. I just live with the hope that someday my time will come.” Although he prefers not to be sentimental for fear of losing what he cherishes, now Samuel considers Hong Kong home. No matter how many challenges he faces, he is grateful for the opportunity to escape the dangers of his country. He concluded, “My only wish for the future is that my children will not have to live my life. Because I made the choice to become a Christian, to leave my country. But for them, this decision of being refugees was made by me.” That thought saddens him immensely.

Contributed by Vania Chow

Profiles of asylum: Burned out of their homes

Sep 13th, 2020 | Personal Experiences, Refugee Community | Comment

Every night, Atif prayed that he would be wrong, that tomorrow would not be what he expected it to be. But, time and again, his prayers proved futile. The first time he saw it happen, he was startled, fearful, angered beyond words. However on that fateful summer evening, as he peered from behind the windows of his living room, all he felt was the sinking sensation of yet another tragedy was about to happen.

First, the fire danced mirthlessly at the base of the house, only leaving imprints of dark char on the brown wooden exterior. It seemed to mock the house and its inhabitants as it moved, taking its time to melt the ornaments that guarded the entrance, reminding the world that nothing was above the power of nature. Outside the house stood three men, the culprits. They seemed to bask in the sinister glow of the burning house, torches and protective gear in one hand and glimmering ornaments on the other.

Occasionally, they would glance around, checking to see if the streets were still devoid of people. It wasn’t that they thought their violence would go unnoticed, but more to seek validation of their power. They sought the glory of being feared, of holding the breath of the neighborhood, of tightening the barbed wire of torment around people’s hearts. If the community, like Atif, so much as raised a finger in protest, their homes would be torched too. Indeed, the house soon succumbed to the siege of fire. The roof cracked and crumbled, spilling onto the very things it was designed to protect with a blazing crash.

With no way out, within the depths of that inferno lay the remains of Atif’s neighbours. Yet Atif could not bring himself to stop watching. In the place of the familiar brown house that stood beside his home for years now stood the smoldering skeleton of a dwelling. The thought of the senseless deaths of his neighbours sent a chill down his spine. The realization grew in him: Today it was them, tomorrow it could be his family. It was only a matter of time, as Atif had committed the same apparently fatal act as his neighbour.

A few days prior, the two men had been summoned to court. The judge called to examine proof of ownership to their homes. The area had belonged to the two families for many generations, not through weighty title deeds, but through the sweat and toil of ancestors settling down on unclaimed land. That is how traditional societies function, through custom and tradition. If someone sold fruits at a street corner for years, that corner was theirs; if someone taught the children of the neighborhood, they were considered the teacher; the same occurred with houses. However, the political landscape had changed and governments took interest in communities previously left alone. Things began to change. The demand to prove land ownership was an example of that.

When Atif and his neighbour shook their heads anxiously before the judge, failing to produce documentation, they were unsure of what would happen. The judge had only nodded. With an air of authority he warned the men that the land they resided on belonged to the government. The judge sat up straight, alas meeting the eyes of the two men with his own narrowed ones; the soldiers at the back tensed, hands tightening on their rifles. The two men, looking at one another, had no choice but to accept the verdict and bring the devastating news home.

As summer faded into autumn, Atif’s cousin was also summoned to court, but unlike Atif, he approached the courthouse with a briefcase brimming with confidence. In the briefcase lay stacks of documents: land leases, water bills, telephone receipts spanning years. Atif’s cousin was in no doubt he would leave the courtroom victorious, having proven the legality of his ownership. But the judge was unimpressed and at first questioned the claim, “Your papers are insufficient.” Atif’s cousin stammered, “But … I can return home to retrieve more if your Honor permits.”

The magistrate seemed lost in thought. Atif’s cousin continued, “I have documents sent to my home from …” The judge raised his stamp and jabbed it inattentively at the papers before him. “That will not be necessary. The house is yours.” The sudden change of mind surprised Atif who realized that he had enough proof to win on appeal had the judge dismissed his ownership. Surprised by this reversal of fortune, Atif couldn’t wait to leave the courthouse before the judge changed his mind. He swung open the main gate, lifted a jubilant foot over the doorstep, and was ready to rush home with the good news.

A few hours later, Atif received news of his cousin’s death. He had been shot nine times at the gate of the courthouse. Documentation or not, the battle for land ownership could not be won. In fact, Atif’s family paid the ultimate price for opposing the powerful people who grabbed their land. Eventually Atif sought asylum in Hong Kong, leaving in Pakistan his parents, uncles and cousins who were all murdered to eliminate their claim to their ancestral land. Today Atif actively supports the Refugee Union and is grateful for the protection his families receives in Hong Kong.

Submitted by Vania Chow

August Roundup

Sep 12th, 2020 | Advocacy | Comment

Refugee Union was founded in 2014 with visions to safeguard protection claimants’ rights and to ameliorate their prospects. Since our commencement of services, we have been working closely with our partners in the community and organising diversified programmes to actualise members’ psychological and social well-being.

Blog Updates and Coverage

This month we are honoured to have a guest contribution on our blog — a piece entitled “Profiles of Asylum: From the Ancient City of Mosul to Hong Kong” which recorded an asylum seeker’s experience taking refuge in Hong Kong, adjusting to tremendous uncertainties in a state of limbo.

We are also thrilled to be featured on Table of Two Cities’ blog — drawing from an everyday life example, Vania Chow in her piece “The Taste of Ice-Cream: Vignettes from Refugee Union” depicted the plight of asylum seekers and refugees in Hong Kong.

Virtual Engagements

In times of COVID-19 pandemic, we are all forced to put face-to-face interactions on hold. With technological advancement, however, social distancing is never a barrier to our solidarity.

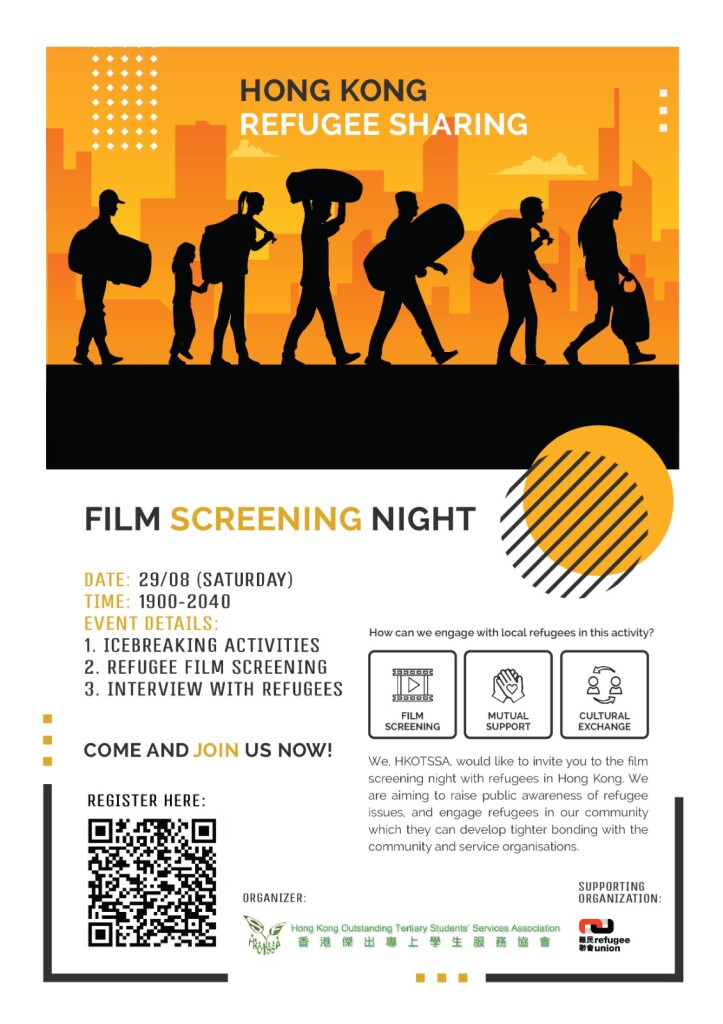

This month we would like to send our acknowledgement to the Hong Kong Outstanding Tertiary Students’ Services Association (HKOTSSA) for bringing us the Film Screening Night in a virtual format. We had a nice evening with you all.

There will be more virtual engagements happening soon, please stay tuned for the updates.

Donations Keep Going

In a difficult time, we would like to express our sincere gratitude to our donors for lending us a helping hand. This month we received donations of different items, which include daily necessities and protective equipment for our members. Thank you very much for our donors’ generous support!

Please stay tuned to our official website and social media pages (Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter) for the updates, and feel free to contact us by visiting our office or sending us an email at info@refugeeunion.org should you have any enquiry.

Profiles of asylum: Anna’s choice

Sep 6th, 2020 | Personal Experiences, Refugee Community | Comment

“Where’s your husband?” The doctor asked as Anna lay on the birthing chair, her hands wrapped tightly around the metal armrest in an effort to calm herself. Anna wasn’t anxious about the procedure, for she had heard all about it from the village midwife, nor was she fearful of the pain, but rather her vexation came from the dreaded phone call the doctor was entitled, in fact obligated to make. “Please!” Anna implored. The nurses cocked their heads aside as if desperate to hear the secrets to be revealed. “Don’t call my husband. He’s not a good man.” Her voice trembled inside the silent delivery room, suddenly accentuating its sullen tension. The doctor glanced at the nurses who averted their gazes, busying themselves with meaningless tasks. He looked at Anna, the young, mid-20’s woman who sat before him, her large brown eyes glistening with tears “Doctor,” she muttered, “these scars are from beatings at home.”

With a gingerly apprehension, the doctor pulled up the hem of the robe, unsure of what to expect. Atop her tan skin were a series of browning bruises, many aligning with fading scars. In the center of this troubling mosaic was a spot that was exceptionally dark in colour and round in shape, almost resembling a hard-boiled egg. The doctor grimaced: this was not the worst he had seen, but it was definitely not a pretty sight. Anna explained, “He pointed his hunting gun at me and hit me with shoes!” Unable to keep up a facade of apathy, the nurses turned to look at the woman in the birthing chair. Some wore an expression of curious sympathy, others that of a weariness that came with a hint of resignation. Perhaps they wondered what atrocities Anna had committed to deserve such a punishment from her husband. “He wants to kill me.” Anna’s voice sliced through the stillness of the room with fragile coldness.

Without a sign of acknowledgement, the doctor signaled to the nurses, washed his hands, put on protective gear, and readied to deliver Anna’s baby. For the first two months, with her newborn baby girl, Anna hid from her husband. She lived in constant fear, staying only within the boundaries of her parents’ house, not daring to interact with anyone but direct family. However, the longer she stayed hidden, the more desperate her husband grew to find her. It was one thing for a woman to disobey her husband, quite another to give birth in secret, running away and hiding their child from him. It was an unspeakable wrongdoing in their traditional community. Anna did not know what would happen if he ever found her and their daughter. She certainly did not wish to find out.

“Mama,” Anna whispered, her supple hands wrapped around her mother’s wrinkly hands. “I can’t live like this.” Her mother’s trusting gaze met Anna’s with a dreaded sense of understanding. “And I won’t let my daughter grow up like this.” Anna felt her mother’s hands tighten around hers before longingly reaching for the warm bundle of a baby that slept in her lap. Without the comfort of the baby in her lap, Anna felt vulnerable and empty. In an attempt to quench the perturbation within, she pushed her clenched fists hard down onto her knees. “I know. You have to go,” her mother whispered, her fingers caressing the baby’s face with a gentleness unique to mothers. “You have my blessing.” Unconsciously, Anna’s hands relaxed and mirrored the soft strokes of her mother’s. Up. Down. Up. Down. After all, Anna was still just a woman of twenty, faced with a situation that would make more experienced women crumble.

Anna’s mind drew a perplexed blank. Before she knew it, she stood at the door of the hut, one hand on its worn bamboo handle, the other clutching her travel documents. She couldn’t take her eyes off the elderly woman and the precious bundle in her arms. Her mother and her daughter meant the world to Anna. They were the two people in her life that she would be willing to sacrifice everything for, whom she loved and trusted unconditionally. Yet there she stood, about to abandon them at their most fragile, when they depended on her the most. Almost in a guilty attempt of self-justification, Anna tried to reason with herself. If she stayed, her husband would eventually find her, and if that nightmare came true, there would be no saying what would happen next …

With that thought, Anna took a deep breath, savouring the familiar smell of boiling milk in the kitchen. She looked around for the last time at the only home she knew, then stepped out the door. As the saying goes, “when one door closes, another one opens”, and for Anna, this was the gateway to Hong Kong. Today, Anna has started her own family in Hong Kong and is the mother to two children.

Submitted By Vania Chow

Hong Kong Refugee Sharing

Aug 25th, 2020 | Personal Experiences, Refugee Community, RU updates, programs, events | Comment

Profiles of asylum: From the ancient city of Mosul to Hong Kong

Aug 6th, 2020 | Detention, Immigration, Personal Experiences, Refugee Community, Rejection | Comment

“Mosul is an ancient city. It was actually called Nineveh before. Have you heard of it?” Alex told me. Most people heard of Nineveh, a Biblical city with a name that echoes across millennia, bubbling with history and myth and revelation and, most recently, a cycle of occupation and violence to match its historic stature. Alex continued, “Before the American occupation in 2003, we could go out with our friends and have picnics outside. It was safe. Some people used to go camping. It was totally safe. It was a good place.”

During 254 days of detention in 2014, Hong Kong Immigration officers at Castle Peak Bay Immigration Centre asked Alex repeatedly why he had left his country. “They suspected that I was a terrorist when they found out I came from Iraq. Then I told them about my past incidents, one with Islamic State, another with the US Army and then another with the Iraqi Forces. I told them life was worse than hell. I think they got scared. Imagine, they don’t know who you are and you have no documents and you’re telling them about life in a war-torn country full of massacres that I witnessed with my own eyes …”

After fleeing from violent conflict in Iraq in April 2010, Alex traveled from Turkey to Cyprus to Malaysia to Indonesia to Singapore to South Korea and finally, in 2014, he reached Hong Kong. Along the way he experienced a series of detainment, interrogations, beatings and the occasional act of kindness. As he described his experiences, he was describing the life of someone outside of the law, someone whose attempts at finding hope and peace are impeded by the structures set up to determine the validity of his claims, structures which deal with him and other refugees primarily as criminals. “What I have faced, what I have suffered, what I have seen … the pain that I’ve felt, it’s really hard to express.”

When a person applies for asylum in Hong Kong, they are administered by the Unified Screening Mechanism (USM), a process designed to determine the validity of their claims. Alex had no passport to prove he was an Iraqi citizen, nor help from an embassy. He explained, “Immigration killed my case. They totally rejected my identity. They said my Iraqi identity is not accepted. They said we can only accept you as an ‘Arabic speaker.’ I mean, does that make sense? I asked them, where am I from?”

So there was Alex, a young man from an ancient city, who had once worked alongside his father installing windowpanes in Mosul’s quiet suburbs, now an undocumented “Arabic speaker” with no recognized history of citizenship or travel due to his decision to leave the very country which makes him a suspect. The choice to flee from violence and to put himself through hardship and uncertainty becomes not admirable and courageous, but suspicious. During his 9-month detention, Alex was humiliated, beaten, and kept in solitary confinement over ten times. He was losing his mind, losing his sense of self and purpose. Alex experienced his lowest points in Hong Kong’s detention system.

“The hardest times I faced were when they kicked me into the solitary confinement cell. That killed me from inside. It made me want to commit suicide. If you look at that cell there’s no window, there’s no one to talk to. It is full of mosquitoes and cockroaches walking on the wall and ceilings everywhere. The lamp in the ceiling was always on hurting my eyes when I tried to sleep. I used to ask the officers to switch it off and they refused. I felt lower than an animal. It felt like they were taking revenge against me for some reason.”

Why is a safe city like Hong Kong so undesirable for those seeking asylum? “In this city I cannot go here and there as I have no money. I mean if I have nothing to do where can I go, what can I do? In Hong Kong refuges are not allowed to work. We are not allowed to have income. We are not allowed to get a bank account, to do any basic things in life.” Then there is the question of hope. More than a decade into exile, Alex is no closer to what he set out to achieve. “I believe anything is possible in this world, but it is hard for me to expect any positive things in Hong Kong. There are a lot of refugees with good skills but there is no encouragement. It seems the government does everything to discourage us and crush our hopes. Basically, they don’t want us to be well.”

Despite this, Alex balances despair with optimism by choosing to face the reality of his situation and his role in managing his physical and mental health. After his release from detention, Alex chose to do for himself what no one could do for him staying positive, keeping healthy and helping those around him. He found a supportive community amongst Hong Kong’s asylum seekers and activists. Through the Refugee Union Alex has met “good people that give me real respect and make me feel like I’m human. There’s no discrimination. There’s no racism. There’s no animosity. There’s no hatred. That’s perhaps what makes me feel that life is still beautiful. Refugee Union has helped me a lot. It’s about how to relieve your stress, how they make sure to create fresh hope in life, not to increase tension, not to make you more depressed, not to make you want to give up. Forget about all your troubles, we’re going to try to help you or at least keep you busy and make you feel that life is still good.”

Even with a community of friends, however, there are limits to how much Alex can allow himself to feel free and at peace. “I really don’t want to focus on my case in Hong Kong any more. I will start to overthink. I will start to worry and get anxious. I mean there are a lot of negative things. It is really better for me just to leave this case aside. Six years in Hong Kong and nothing has moved forward. I lost hope in Hong Kong Government. I really don’t have any hope for another opportunity.”

(written by Pedro Cortes)

JULY ROUNDUP

Aug 5th, 2020 | Advocacy | Comment

Refugee Union was founded in 2014 with visions to safeguard protection claimants’ rights and to ameliorate their prospects. Since our commencement of services, we have been working closely with our partners in the community and organising diversified programmes to actualise members’ psychological and social well-being.

Our Featured Articles

This month we are thrilled to be featured in two articles. Sophia Zhang from Shatin College wrote about the stories of asylum seekers and refugees in Hong Kong based on her interviews with our members. Her article has been published on our blog. Ka Wang Kelvin Lam, our volunteer and a researcher of the Department of Sociology at the Chinese University of Hong Kong (CUHK), highlighted the importance of the refugee community. He wrote about the ways asylum seekers and refugees here cope with hardship in times of COVID-19 pandemic by using our organisation as a case study. His article has been published with Routed Magazine and the blog of the University of Oxford’s Centre on Migration, Policy and Society (COMPAS).

Stop Indefinite Detention

We are aware of the indefinite detention happening in the Castle Peak Bay Immigration Centre (CIC). Without a reasonable justification, such an act sharply differs from the general practice of the Immigration Department on arrest and detention, not to mention other issues (say, hygiene and delayed medical treatments) the detainees are suffering from. Among them, some are asylum seekers and refugees. They are currently in a hunger strike going against CIC’s indefinite detention. All lives matter. With the CIC Detainees Right Concern Group, we the Refugee Union always stand with the detainees and condemn all inhuman treatments.

Donations Keep Going

The coronavirus disease continues to surge Hong Kong and across the globe. In this difficult time, we would like to express our sincere gratitude to our donors for lending us a helping hand. This month we received donations of different items, which include daily necessities and protective equipment for our members. Thank you very much for our donors’ generous support!

Please stay tuned to our official website and social media pages (Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter) for the updates, and feel free to contact us by visiting our office or sending us an email at info@refugeeunion.org should you have any enquiry.

Meeting refugees at the union

Jul 15th, 2020 | Personal Experiences, Refugee Community | Comment

Tom* sought asylum in Hong Kong twenty years ago. He is from Pakistan and met his wife here during this time. They now have four children (16, 10, 8, 5 years old) – all asylum-seekers. While Tom used to work in construction back home, he has not been able to work at all in Hong Kong. Under the city’s law, refugees are banned from working, though many choose to pursue illegal jobs to make ends meet. However, in response to this, Tom said: “I cannot pursue illegal work, I do not dare – what will happen to my wife and children if I go to jail?” But without employment, living in limbo has taken a toll on him: “My life is empty,” he tells me, “Twenty years. I’m wasting my time. I only bring my children to school and back, nothing else to do.” There are tears in his eyes as he speaks and I have to look away.

When asked what the most difficult aspect of refugee life is, Tom sighs: “Life is hard here because everything is so expensive.” Just recently, his youngest daughter’s school decided to change the uniforms. However, he could not afford the new uniform and had to ask the school if they could delay the payment for a month. Luckily, the school was able to let Tom’s daughter stay in school, but Tom frets over where to find the money for the fees. Refugees live on a scant $3200 monthly from the government, often finding themselves lacking sufficient income. Parents, like Tom, are under enormous pressure to provide for their children in the notoriously expensive city of Hong Kong.

Yet many have also found solace in this city. Hannah* is a Ugandan refugee: “I came to Hong Kong hurt and broken,” she says. Hannah has since converted from Islam to Christianity, which played a pivotal role in her life: “I would have been dead, but God heard my prayers.” Though initially her life in Hong Kong was difficult, Hannah has now found a community at her church, friends who supported her when she was admitted to hospital and money for treatment was scarce. “If you believe in God, anything is possible,” she beams, “I’ve let go of my troubles. I appreciate what I can achieve. I know God has a plan.” Hannah now volunteers at the Refugee Union, a place she describes as a safe haven that listens to the voices of the marginalized. “How can I not help when they’ve helped me?” she asks. “Everyone should put their feet in another person’s shoes and feel their life.”

Anne* is also an Ugandan refugee, once a teacher back home. She came to Hong Kong a decade ago in search of safety away from the authoritarian regime under Yoweri Museveni. “The big difference between Uganda and Hong Kong is that here there is security and the rule of law. In Uganda, people go out one day and don’t come back. People die silently. I had to leave. If you have any power, you must. If you don’t find a way out, you will be dead.” Anne herself had her land and property taken away forcefully by the government. She cannot return to Uganda as she fears she will be labelled a terrorist and thrown in jail and possibly tortured. “We are trying to tell the truth, but now we are the government’s enemies,” she shakes her head.

Under the iron fist of the dictator, corruption, censorship and violence plague Uganda. “Uganda shouldn’t be a poor country. It is only because of poor leadership and management. The President doesn’t develop the country at all. He came to steal, kill, destroy and spoil our future. He treats human lives as a business.” As a mother back home, Anne finds it painful to watch the news, because it reminds her of her family and her people. “We’ve lost our futures, we’ve lost everything. In our heads, we are still connected to Uganda. Sometimes we become insane thinking about this. I cry in my sleep, because all I want is for my people to be safe and to be free. Is that too much to ask?”

* names were changed for privacy reasons

Written by Sophia Zhang (16) – Shatin College